Fireworks and Fraud Close Out 2022 | Decentralized Law

A Journal Covering the Crypto-Legal Space

Dear Crypto-Legal Observers,

In some ways, you have to ask yourself: who would want to do a review of 2022 for the cryptoverse? Crypto winter, a bear market, bankruptcies, fraud, and the collapse of entire ecosystems. More than a few crypto founders are on the run from authorities, and it appears that sensible crypto regulations are still largely a thing of daydreams.

But in order to move forward, we must reconcile with the past. William Faulkner famously wrote, "The past is not dead. It's not even past”. Like Charles Dickens’ famous Christmas ghost, UK crypto attorney G0xse gently leads us through the travesties of last year while reminding us that practical things, like good corporate governance and regulations, would have prevented many of these situations. Not even the blockchain can stop ‘good old-fashioned’ fraud, of course, but benign neglect of blockchain-based systems from many nations hasn’t helped.

The fact that much of crypto still operates in a regulatory gray area is perilous to projects and protocols, let alone founders, investors, employees, and contributors. Yet, this uncertainty has given rise to a stellar class of crypto lawyers who can advise one client on the ‘ins and outs’ of NFTs and intellectual property and for another suggest complex strategies for multi-jurisdictional DAO structures. The modern crypto lawyer hangs her shingle in the metaverse and gets ready to work, and no one personifies this can-do-it-all archetype better than Jordan Teague.

Jordan is the co-founder of The Antifirm, a crypto-focused law firm, and currently serves as General Counsel for The Graph Foundation. Oh, and she is also a Solidity developer and co-founder of Kali, a no-code DAO platform that we’ve previously covered in Decentralized Law.

Jordan may already be able to write a smart contract, but she rightly highlights the importance of getting your hands on technology to really understand how it works — advice that applies not just to crypto attorneys, but to everyone:

In my opinion, everyone could benefit from learning some coding basics, but you don’t need to learn to code to be a great crypto lawyer. Whether it’s getting involved in DAO governance, playing with DeFi protocols, or trading NFTs, there are many ways to engage with web3 — and that hands-on engagement is what’s going to give you the edge.

Besides this sage advice, in this issue of Decentralized Law we review the common threads weaving together 2022’s troubles, provide a primer on bankruptcy clawbacks through the lens of FTX, re-examine attorney-client privilege in the digital age, analyze the nexus between NFTs and money laundering, and summarize news and articles from throughout the cryptoverse.

Although this newsletter may help to familiarize readers with the legal implications arising out of blockchain technology, the contents of Decentralized Law are not legal advice. This newsletter is intended only as general information. Writers' opinions are their own; therefore, nothing in this newsletter constitutes or should be considered legal advice. Contact a legal expert in your jurisdiction for legal advice.

Welcome to Decentralized Law.

Contributors: eaglelex, COYSrUS, Trewkat, Cheetah, pub-gmn.eth, Svetlink, lawpanda, G0xse, Oluwasijibomi, KingIBK, ximpli_ana, Aloy, BOBOtoTHEmoon, hirokennelly.eth

This is an official legal newsletter of BanklessDAO. To unsubscribe, edit your settings.

🙏 Thank You to Our Partner

Polygon Village - A full-stack ecosystem for developers to build and grow.

🎙 Interview

Jordan Teague Sets the Bar High

Please tell us something about your background and how you started to engage with crypto-legal issues.

For some background, ever since I was 9 years old, one of my favorite hobbies has been coding — everything from simple websites to SaaS products to iPhone apps. Sometime in 2021, I became motivated to learn Solidity and smart contract development. I’d heard plenty about crypto prior to then, and I knew in theory that smart contracts would revolutionize the legal field — but it wasn’t until I started writing Solidity, deploying code, and interacting with dApps on MetaMask that I really “got it.” Rolling up my sleeves and playing with the technology helped me fully understand what makes a decentralized blockchain network unique from web 2.0 and why it matters. The passion for the technology turned me into a zealous advocate for crypto and got me engaged on the legal side of things.

What makes you so passionate about blockchain technology?

One big reason is the potential for decentralization and disintermediation. Over the last several years, we’ve seen what happens when too much power is concentrated in the power of a handful of intermediaries. Social media giants, for example, can de-platform a user on a whim for supposed “terms of service” violations with little recourse available to the user. Relatedly, I’m rooting for decentralized social platforms, such as Lens Protocol, which stand to put users in control of their data and social graphs.

You are the rare crypto lawyer who can also code, including Solidity, the language of Ethereum smart contracts. What advantages does that give you and your clients when crafting legal solutions?

Learning Solidity has definitely given me an advantage as a crypto lawyer, but I believe that’s primarily because coding is a way for me to engage with the technology and understand it more deeply. In my opinion, everyone could benefit from learning some coding basics, but you don’t need to learn to code to be a great crypto lawyer. Whether it’s getting involved in DAO governance, playing with DeFi protocols, or trading NFTs, there are many ways to engage with web3 — and that hands-on engagement is what’s going to give you the edge.

For any lawyers out there who want to learn some Solidity, get involved in LexDAO! We do a weekly ‘hacks’ call where we teach some basic Solidity. There are also lots of opportunities to roll up your sleeves and collaborate with LexDAO members on projects.

You are one of the most vocal critics of the Wyoming DAO LLC law. What do Wyoming and other jurisdictions need to do better?

Although it’s encouraging to see states like Wyoming and Tennessee recognize the value of DAOs through legislative efforts, ultimately, these DAO LLC statutes feel like solutions in search of problems. I go into greater detail in my article in The Defiant, but the Wyoming and Tennessee DAO LLC statutes are narrower versions of the traditional LLC, with added burdens and no additional benefits. This begs the question, why would a DAO choose a “DAO LLC” over a plain old LLC (or some other entity type)? I’d recommend that states considering DAO legislation approach the matter from first principles. What problems are we trying to solve? How can we set DAOs up for success with a new entity type better than with an existing one? As a starting point, here’s one practical suggestion: eliminate unnecessary “IRL” stumbling blocks for DAOs. That could include, for instance, allowing the registered agent requirement to be fulfilled in a digital way, or enabling DAO entities to form in a crypto-native way (such as on a blockchain-based registry).

NFTs and IP law were in the news a fair bit last year, whether derivative art lawsuits or CC0 licenses. Do NFTs fit nicely within the current intellectual property regime in the U.S., or do we need to rethink property rights for the blockchain age?

While the NFT community has gotten savvier when it comes to NFTs and IPs, there was a lot of confusion at the height of the NFT bull run. Remember when Seth Green’s Bored Ape got stolen? Many speculated that Green would have to cancel a TV show he’d produced based on his NFT — the rationale being, since he lost his Ape, he lost the IP. But if you dig into the BAYC Terms and Conditions, BAYC grants a commercial license to any holder of the NFT. Nothing in the Terms stated that the license would terminate upon transfer of the NFT. Thus, even if Green had willingly transferred the NFT, it’s not clear that the license would have terminated.

Although the IP to Green’s Ape was not tethered to the NFT, there does seem to be demand for a “bearer instrument” copyright, that is, copyright which can be transferred simply through transfer of the associated token. Existing copyright laws make this challenging (for example, the U.S.’s “signed writing” requirement for assignments). It would be interesting to see laws evolve to accommodate bearer IP rights for digital assets.

MakerDAO underwent massive changes in 2022, largely over disputes about real world assets and using those to secure Maker vaults. In general, what are the concerns around real world assets and how off-chain collateral integrates with what we do on chain?

Those of us who are “all in” on crypto believe that authoritative property transaction ledgers will one day live on chain. But we don’t live in that world quite yet. Real property records, the UCC, IP registries, and the like are still maintained off chain by government agencies. This means that no matter how hard we try to tokenize real world assets, we can’t yet escape the need for parallel off-chain action.

For example, I could tokenize my house deed and sell it. Unless that NFT transfer triggers a recording of the sale with the local register of deeds, there’s a chance that a subsequent off-chain sale to another purchaser might take precedence over the earlier on-chain transaction. (Of course, that’s shady, and would be called fraud, but the first purchaser may still be without a house.)

Thus, so long as we’re living in this in-between, “web 2.5” world, it will be necessary to think about how to integrate with off-chain sources of authority. However, I’m optimistic that one day we’ll see deed records and other property registries go on-chain, such that in my above example, the NFT transfer itself would be the source of authority that the property sale occurred.

“Code is Law” is one of those terms thrown around the crypto-legal sphere. What’s the really basic idea behind this maxim?

The basic premise of “code is law” is that if a smart contract permits something to occur, it is “legal.” After all, the smart contract could have been written to prevent the thing in question from occurring. Code-is-law maxis would argue that even hacks or unexpected behavior should be considered “legal.” Of course, it’s easy to wave the “code is law” banner until you lose millions of dollars due to a security flaw or an economic exploit.

Famously, the Ethereum blockchain forked into ETH/ETC after a re-entrancy attack that resulted in a $60 million loss. This was because the majority did not believe code was law in that instance. You would likely never see a similar hard fork today since re-entrancy attacks are a well-known vulnerability. Might this suggest a majority view that code is usually law, unless the results of such code defy our reasonable expectations?

A recent example of the “code is law” debate is the Mango Market exploit, where Avi Eisenberg and others gamed the protocol’s economic model, enabling them to withdraw over $100 million. Avi called this a “profitable trading strategy”; unfortunately for Avi, the DOJ believes otherwise. This will be an interesting case to watch (assuming it advances beyond a quick settlement) to see how the “code is law” maxim is received by courts.

Personally, although I am a coder and a big believer in taking a code-deference approach to lawyering, I do not believe our society is ready to accept that “code is law,” full stop. If we were, then I suspect it would not be considered theft to walk into your neighbor’s house and take their jewelry if they forgot to lock their front door. It will be interesting to revisit this in 20 years and see what has changed!

Jordan is a lawyer who co-founded The Antifirm, a law firm serving clients in the crypto space, and currently serves as General Counsel for The Graph Foundation, the steward of The Graph protocol. Jordan is also a Solidity developer and a co-founder of Kali, a DAO platform.

⚖ Developments

FTX and the “Crypto Clawback”

Author: lawpanda

Did you see this tweet?

While Balaji is correct about the importance of learning some of these terms in light of multiple failed centralized exchanges which are seeking protection in bankruptcy, he’s not quite correct about how the bankruptcy system operates, as noted by Van Brooks in a reply to Balaji’s tweet:

Customers who withdrew their crypto assets in the ninety days before FTX filed for bankruptcy could be sued by the company's creditors to get the money back. This is called a ‘clawback’ under the bankruptcy code. A clawback is a broad term for the right of the bankruptcy trustee (also sometimes known as the Debtor in Possession or DIP) to seize funds transferred to creditors preferentially or through fraud. The goal of clawbacks, and ultimately of the Bankruptcy Code, is to ensure a fair outcome for creditors as a class. To accomplish this, the DIP may void deals retroactively and recoup debtor funds by recovering funds from transactions and transfers made within a certain period of time prior to the filing of the bankruptcy petition. Funds that are recovered are returned to the bankruptcy estate’s coffers with the goal of eventually giving creditors the largest possible recovery, distributed evenly among all creditors.

FTX’s Insolvency

On November 11, 2022, FTX Trading Ltd. announced it had filed a voluntary petition for bankruptcy under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware. The filing includes 134 “debtor entities,” functionally the full FTX corporate group (referred to as FTX throughout this article). This means that the bankruptcy court is now in charge of managing and reorganizing the FTX group. Over the next few months — or potentially years — all of the debtor group's assets will be managed for the benefit of FTX's creditors. It's important to know that, unlike Chapter 7, Chapter 11 enables FTX to come out of bankruptcy and keep operating in some way in the future.

In the weeks preceding the filing of the bankruptcy petition there were — not unexpectedly — a significant number of crypto asset withdrawals from the exchange. A Twitter thread by the blockchain research group Arkham Intelligence lists the largest withdrawals from FTX in the days leading up to the bankruptcy. That report shows that trading firm Jane Street managed to withdraw $27 million worth of crypto assets from FTX on the eve of bankruptcy. While it might seem that Jane Street and other customers who were able to withdraw their assets from FTX have dodged a bullet, they are not necessarily in the clear.

Under the bankruptcy code, the date of insolvency is 90 days before the bankruptcy petition is filed. This means that customers who used and withdrew funds from entities in the FTX debtor group, organizations that received investments and political donations, and vendors receiving payments from approximately August 11, 2022 onward, may have any assets received clawed back into the bankruptcy estate. This timeframe extends to one year in the case of ‘insiders’ and in instances where there are allegations of fraud — including a determination of a Ponzi scheme — the period of time over which funds may be clawed back can extend beyond that. At this point, it is hard to say whether any funds will be clawed back. However, if a transaction occurred within the relevant time period, the recipient will eventually receive a notice from the bankruptcy court, and this is the starting point to mount a defense, negotiate a settlement, or engage in litigation.

Preference Claims

There are two main types of clawback processes: preference actions under Section 547 of the Bankruptcy Code and fraudulent conveyance actions under Section 548. Preference and fraudulent conveyance claims generally encompass larger transactions — as opposed to transactions by retail customers — that could appear irregular, even if the recipient did nothing wrong and had no knowledge of any potential impropriety.

A preference claim under Section 547(b) of the Bankruptcy Code permits the trustee to recover or avoid preferences. The law presumes that payments made in close proximity (generally ninety days) to the debtor's insolvency gave the recipient preferential treatment over the debtor’s other creditors. A preference action attempts to undo the preferential payment and return funds back into the estate so they can be distributed equally to all creditors. As noted above, for the FTX debtor group this would include all transactions from approximately August 11, 2022, until the filing. However, if the debtor paid insiders or helped insiders remove assets from the estate, the trustee can claw back those assets within a year of the filing date. This means that preference actions in those specific instances could go as far back as November 2021. Additionally, the trustee has two years from the petition filing date, or until November 11, 2024, to commence any preference actions.

Generally, preference rules do not take the recipient’s intent or knowledge into account. This means that if a large FTX customer closed their account in the preference period, without knowledge of the upcoming bankruptcy, the money could still be clawed back. The purpose of a preference action and the bankruptcy code as a whole is not to punish those who received funds, but rather to promote fairness to all investors and creditors by making those that received money just before the collapse return the money and be treated like all other investors.

Some examples of preferential transfers include payments made within the 90-day period before the filing of a bankruptcy petition:

on an invoice that is substantially overdue; the payment is considered preferential because it is made to ensure continued service or delivery of goods.

of all outstanding invoices owed in a lump sum payment when the debtor generally pays each invoice separately on a monthly basis.

of a debt immediately upon incurring the debt when the debtor generally pays the debt within a period of time after receipt of the invoice.

In each instance, the ‘preference’ to the creditor that received the funds is apparent because the payment allows one creditor to receive more than other similarly situated creditors. Alternatively, payments that appear outside of the ordinary course of business between the parties will trigger a preference assessment.

Fraudulent Conveyance and Ponzi Schemes

The second type of clawback is a “fraudulent conveyance claim” under Section 548. These clawbacks target transactions that occurred up to two years before the bankruptcy petition was filed. Fraudulent conveyance claims require an allegation that the debtor moved assets out of the estate for the purpose of frustrating future creditor claims. Fraudulent conveyance claims are more difficult to prove and more individualized to the specific transaction.

There are two types of fraudulent conveyance claims available to the trustee. The first — and more common claim — is constructive fraud based on the receipt of money or assets from the debtor without having provided anything of reasonably equivalent value in return. Fraudulent conveyance claims do not require intent to defraud by the recipient; they just require receipt of the debtor’s assets without having provided the debtor with anything of appropriate value in return.

The second type of fraudulent conveyance claim requires some proof of the recipient's understanding that it was improper to receive the assets. In the context of a Ponzi scheme and its investors, the issue of reasonably equivalent value focuses on whether the investor is withdrawing more or less than originally invested. The original investment constitutes value given to the debtor, so withdrawals of the original investment are not subject to fraudulent conveyance claims — at least as long as the investor had no reason to know about the fraud. However, if more than the original investment is withdrawn, the investor’s withdrawal of the false profits generated by the Ponzi scheme is considered a withdrawal of another investor’s principal investment and is subject to clawback by the estate.

There have been some comparisons of FTX to the Madoff case; however, it is not yet clear whether FTX’s bankruptcy will be qualified as a Ponzi and subject to that form of clawback. Classification of the estate and conveyances as a Ponzi could significantly extend the life of bankruptcy proceedings. As of September 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice commenced its eighth distribution to Madoff victims since 2009, and efforts appear to be ongoing. Part of the theory behind a Ponzi determination is that the debtor never operated a legitimate business through the scheme, and accordingly, all of the payments that were made to investors were made with other investor funds that should be recovered for pro rata distribution to all the investors.

If FTX was started as a legitimate exchange and custodial trading platform and operated in that manner for an unspecified amount of time before allegedly misappropriating client funds, then it may ultimately be determined not to be a Ponzi. However, it is also notable that the CFTC and SEC have both seemed to allege that FTX was a “fraud from the start,” which seems to foreshadow the approach of their civil and criminal actions against FTX and may ultimately impact the way bankruptcy and civil forfeiture clawback efforts proceed.

Are Assets Property of the Customer?

The user agreements and other contracts between centralized exchanges like FTX and their users may determine what happens to customer funds in the event of bankruptcy. In a preference assessment, it is often important to know whether the customer or the exchange holds title to the assets that are held on the exchange. If assets that are withdrawn are not considered exchange property, then those assets cannot be clawed back from customers. The court may even direct the bankruptcy estate to transfer assets back to customers. Generally, whether crypto assets are property of a bankruptcy estate is a fact-specific determination and depends on several factors, including the terms of the customer agreement and how the crypto assets are held. As noted above, if title to the crypto is with the customer, the assets may be outside of the estate and remain the property of the customer.

Precedent From Celsius Bankruptcy Proceedings

Celsius is another large crypto exchange that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in July 2022 in the Southern District of New York. According to a September 2022 filing, approximately 58,000 users held assets worth $210 million in Celsius’ “Custody” program. Of those customers, there were approximately 16,000 who held $44 million in what is known as “pure custody,” meaning those funds were never deposited in the yield-bearing “Earn” program. At the December 2022 hearing, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Martin Glenn ruled that the “pure custody” group retained title to the assets and that those assets would be returned to the customers — and implicitly that those assets would not be subject to preference actions in the future.

Here, the ownership and title to the Custody Assets should be determined by the parties’ respective contractual rights, as articulated in the Latest Terms of Use, which are clear and provide ample evidence that the parties’ intent was that the title and ownership of Custody Assets remain with the customers, and that title and ownership of assets in the Earn Program and the Borrow Program are held by the Debtors.

In a January 2023 ruling, Judge Glenn confirmed that Earn and Borrow program assets were property of the estate. For those programs, the terms of service allowed for rehypothecation of the assets in exchange for yield and “unambiguously transferred all right and title of digital assets to Celsius.”

With respect to similarly situated FTX customers, according to FTX’s terms of service, title to customer crypto assets on the FTX platform remains with the customer and does not allow for rehypothecation. And, while Southern District of New York bankruptcy rulings are not binding precedent in Delaware District bankruptcy cases, Judge Glenn’s ruling can act as persuasive authority when this issue arises in the FTX case. However, one significant distinction between the Celisus and FTX cases is that FTX’s apparent misuse and co-mingling of custodied customer assets across the FTX debtor group may simply mean there are no readily identifiable customer assets to return.

Investments by FTX Ventures and Alameda

Notwithstanding issues relating to custody and trade of funds on the FTX platform, FTX pumped billions of dollars into startups and venture capital funds in the two years prior to its insolvency. This spreadsheet, first shared by the Financial Times, shows Alameda Research’s private equity portfolio, which includes nearly 500 investments amounting to $5.276 billion. This matters in the context of bankruptcy because the recipients of those investment funds are likely wondering what could happen next and if that money could be clawed back. The Financial Times spreadsheet does not indicate when investments were made, but for those made outside the 90-day insolvency window, the investments may not be preferential transfers because there is usually no debt attached to startup stock investments (in the form of SAFEs, SAFTs, etc.). For the investments to be clawed back as fraudulent conveyances, the trustee would need to demonstrate that the investments themselves were not made at fair market value (regardless of whether or not that value has since declined). It is also relevant that invested FTX funds or assets are likely no longer available but exist in the form of resultant assets, such as equity, digital tokens, or limited partnership positions.

FTX Political and Charitable Contributions

Notwithstanding all the partisan political posturing relating to FTX political contributions, at least some amounts of the contributions are subject to the clawback provisions discussed above. At least $73 million in political donations are tied to FTX. If it is determined that fraud is involved, then nearly all donations tied to FTX could be targeted for recovery. If there is no determination of fraud, there still appears to be at least $8.1 million subject to the 90-day insolvency period.

FTX also apparently made significant contributions to the Effective Altruism community over the past several years. In a post on the Effective Altruism Forum, the effects of FTX's bankruptcy are discussed in depth. The poster appropriately points out that received funds should be segregated to the extent possible and remain so, not to be returned until some notice from the bankruptcy court is received.

Potential Defenses to Clawbacks

As discussed in the opening, individuals in receipt of any FTX funds determined to be preferential or subject to fraudulent conveyance will eventually receive a notice (and/or be served with a lawsuit) from the bankruptcy court. The crucial questions for most customers facing preference suits will be whether 1) the withdrawn crypto assets belong to the debtor or to the customer, 2) whether an affirmative defense applies, and 3) whether the safe harbor provisions for securities and commodities trading apply. Some examples of these defenses include:

Section 548(c) of the Bankruptcy Code allows investors to assert a good faith defense should there be a determination that the debtor operated a Ponzi scheme. Good faith is generally measured under an objective prudent investor standard.

Section 547(c) of the Bankruptcy Code sets forth nine separate affirmative defenses that a creditor can assert in response to a preference claim. The most common include:

The subsequent new value defense, where new value is defined as “money or money’s worth in goods, services or new credit . . . .” Section 547(c)(4) allows a creditor to offset new value provided against a preferential transfer.

The ordinary course of business defense under Section 547(c)(2) allows a creditor to assert payments it received from the debtor were made in the ordinary course of business. For example, payments made by invoices are generally not preferential unless the terms of the invoicing changed in response or close to insolvency. For crypto exchange customers, this is a fact-specific inquiry and considers the terms of the service agreement, time spent as a customer, and the size, timing, and circumstances surrounding the customer’s withdrawal. Situations where there appear to be “run on the bank” withdrawals in reaction to negative media are generally indicative that withdrawals were not made in the ordinary course.

The contemporaneous exchange for new value defense under Section 547(c)(1) provides for a determination that the creditor extended new value to the debtor via contemporaneous exchange. As with a subsequent new value defense, the contemporaneous exchange defense provides an offset only to the extent of the new value given.

The safe harbor defense under Section 546(e) exempts certain transactions involving securities and commodities contracts. This defense is subject to a determination regarding whether the asset in question is a security or a commodity, among other factors further discussed here.

Ultimately, given the complexity of the legal issues implicated as the bankruptcy process unfolds, it is most important to seek the advice of knowledgeable counsel. The docket contains further information regarding overall process and relevant deadlines and this author has also written a primer about the initial creditor claim process.

lawpanda is a U.S. attorney with an active litigation and counseling practice assisting builders, developers, traditional companies, and decentralized communities. He is a member of BanklessDAO’s Legal Guild, LexDAO, LeXpunK, the Blockchain Lawyers Group, and member/consultant/contributor to a variety of DAOs and protocols. When he’s not writing for Decentralized Law, he is working to reduce operational and governance friction between on-chain and legacy entities through corporate structuring and common-sense legal solutions. Read his scribblings on Mirror and connect on Twitter, LinkedIn, or at lawpanda.eth@gmail.com.

“Never Send To Know for Whom the Bells Tolls…”

Author: G0xse

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.” John Donne

As the year 2021 came to an end there was so much optimism about the crypto ecosystem. New projects with the potential to bring transformational change were springing up daily. Older projects were gaining traction, starting to make a name and build a legacy. It seemed the ecosystem was on the cusp of a big boom and 2022 was looking great.

Then the bells began to toll …

February 2022: Canada Bans 34 Crypto wallets Tied to Freedom Convoy. Certain wallets, which allegedly contained approximately $1.4 million in cryptocurrency, were frozen following the enactment of an Emergency Act that allowed for them to be frozen without a court order.

February 2022: Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine saw crypto become a key focal point in the subsequent war, as Russia came within the purview of global sanctions and supporters sent crypto to troops in the Ukraine.

March 2022: hackings were rampant. Although this was not new to the ecosystem, the amounts lost were staggering. Axie Infinity’s Ronin bridge Network was targeted in a hack and approximately $551.8 million was lost. The Crypto Briefing’s review of 2022 notes that “The strangest detail of the whole incident is that the hack occurred six days before the news broke. For almost a week, nobody managing the bridge or providing liquidity realised the funds had been drained.”

May 2022: Terra, which had created a name for itself in 2021 and held big hopes for 2022, crashed. The TerraUSD and LUNA tokens tanked. Terra’s collapse impacted several crypto platforms such as Celsius, Three Arrows Capital, and Genesis Trading, and raised additional questions about the regulation of the ecosystem and the impact of stablecoins on global financial stability.

June 2022: as a result of Terra’s collapse, both Celsius and Three Arrows Capital filed for insolvency.

August 2022: Tornado Cash was placed on the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) Sanctions list and Tornado Cash core developer Alexey Pertsev was arrested in the Netherlands on suspicion of facilitating money laundering.

September 2022: the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) started an enforcement action against bZeroX (Ooki DAO) governance token holders

November 2022: the bells tolled for FTX, resulting in FTX and FTX.US filing for bankruptcy on 11 November, 2022. The impact of the FTX crash on the market has been enormous and the fallout is ongoing. Just as with Terra, the FTX crash has produced strong ripples, in this case reaching cryptocurrencies it invested in, such as Solana, and firms it did business with, such as BlockFi, which filed for bankruptcy on 28 November, 2022.

When Satoshi Nakamoto published his white paper titled "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” in October 2008, the intent was to advocate for the creation of a transactional system that was transparent and could operate free from centralised control. The key rationale behind this concept was the premise that when decision making lies in the hands of a few people, problems are more likely to occur. To quote Alex Tapscott, co-author of Blockchain Revolution and co-founder of the Blockchain Research Institute, despite this intent, we have with FTX “….. exactly what Bitcoin’s creator Satoshi Nakamoto sought to route around: a centralized organization that used its clout to take excessive risks in a loosely regulated market. In the end, retail paid the heaviest toll.”

While I accept that it would be wrong to tar every innovation with the same brush as FTX, I strongly believe that there is no better time than now for founders, their teams, and advisers to ask more of each other as they work, to innovate and build platforms that address the issues of inefficiencies, lack of transparency, limitations to access, centralised control, and low interoperability prevalent with current financial systems. I also believe that the more all players in the ecosystem fail to ask questions and call out bad actors when we come across them, the more these failings that have enormous ramifications will continue to happen.

For the ecosystem to survive and, dare I be so bold as to say, thrive, following the recent turbulent times, it must do two things in the months to come. Firstly, it must convince its users that although it may on occasion have to adopt centralised structures to scale, it will do so in a manner that is stable and dependable. Secondly it must convince all players — consumers and regulators alike — that it can be both transparent and trustworthy. In achieving this, it must pay attention to two key threads that seem to run in parallel in most of the events of 2022. These are (i) the need for oversight and some form of corporate governance and (ii) a lack of legal and regulatory clarity.

(i) The Need for Oversight and Some Form of Corporate Governance

In his assessment of the failings of FTX its new CEO, John J. Ray III, was very vocal about its corporate governance failings, stating:

Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here. From compromised systems integrity and faulty regulatory oversight abroad, to the concentration of control in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals, this situation is unprecedented.

The drive to build, innovate, and scale can no longer be at the expense of stable and accountable structures that foster growth. Although some founders lead or manage platforms brilliantly, not every founder is equipped to lead, manage, or act as CEO of a company. As John Donne puts it: “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” We all have a part to play, and as founders build, we should hold them and their teams to a higher standard of capability, integrity, and expertise. My ask to founders by extension is this: if you are unable to effectively lead or manage a company, stick with creating the vision but get yourself a reliable ‘kingmaker’ — a trusted adviser(s) and someone who can challenge your ideas for the growth of the business and the day to day running of the same, and who can push for some form of corporate governance.

The concept of corporate governance — the system underpinning how companies are directed and controlled — is nothing new. In asking for a push towards corporate governance, my ask is not for this to be prescriptive in form, especially in a developing ecosystem such as crypto. As advocated by the UK Financial Reporting Council in its article of February 2021 titled 'Improving the quality of ‘comply or explain’ reporting’, the end state should be a corporate governance system that will allow “the companies to develop governance processes and practices that are the most suitable for their particular circumstances and to report them in a meaningful way”. The application of the processes and practices may be different across regions but at their core they should incorporate some key principles such as responsibility, transparency, accountability, risk management and fairness that can be applied across the organisation. Most importantly, governance should extend beyond the vision and strategic aims of the company, which is where most founders and their teams tend to focus, and include fundamental structures aimed at improving transparency and accountability within existing systems.

In a time of regulatory uncertainty — with regulatory expectations and requirements evolving or in some cases non-existent — it can be difficult to get good governance right. Nevertheless, there are best practice rules out there that encourage responsibility, transparency, accountability, risk management and fairness which founders, CEOs, their advisers, and their teams can adopt and apply as they innovate.

(ii) A Lack of Legal and Regulatory Clarity

Moving on to the issue of regulatory clarity, one advocate for stricter regulation of the crypto ecosystem is Sir John Cunliffe, Deputy Governor of Financial Stability for the Bank of England. He proposed in his speech titled ‘Reflections on DeFi, digital currencies and regulation’ that in considering regulation for the crypto ecosystem the guiding principle of ‘same risk, same regulatory outcome’ should apply. He states that “the starting point should be our existing regulatory frameworks – for investment products, for exchanges, for payments systems and other financial functions”. Considering the loss borne by retail investors in 2022, one must somewhat agree with him. However, the pertinent question would be whose regulatory framework should apply?’ America, Europe, United Kingdom, Singapore, Bermuda, Bahamas…? The list goes on.

Finding the right regulatory balance in such a quickly evolving ecosystem will always be difficult. The technologies on which the systems run are not national or tied to one jurisdiction. They are global. They are cross-border, resulting in a mixed and fragmented regulatory framework. This inefficiency has meant that in some jurisdictions regulators have taken an exceptionally hard stance and thereby killed innovation, and in others they have been too lenient, resulting in the exploitation of consumers. Campbell Harvey made this point very clearly in his paper for the CFA Institute titled ‘DeFI Opportunities and Risks’.

Consequently the focus should not just be on regulation for regulation’s sake but on regulation that is fit for purpose. One school of thought is that which is advocated by Howell E. Jackson, in his article Substituted Compliance: The Emergence, Challenges, and Evolution of a New Regulatory Paradigm (2015) written in the Journal of Financial Regulation. He advocates for a principle of regulation based on the concept of “substituted compliance” or equivalence which exists within the specific context of the European Union’s passporting regime. The principle works on the premise that once a DeFi project is licensed in one jurisdiction, other jurisdictions could (and should) recognise its supervision in the home jurisdiction and reduce their own regulatory requirements. The basis for this recognition is that the financial legislation and supervision in the home country has substantially the same effects as the legislation and supervision in the host country. Jackson does concede that while this is simple in theory, substituted compliance is a concept that has proven difficult to achieve in practice outside the EU context. My view is that there is some merit in its adoption, or perhaps in the adoption of a hybrid version of it, where the regulatory requirement is not determined by country lines but possibly by regional/ continental lines.

Regulators have shown that they are capable of doing this and have managed to do so effectively following the 2008 global financial crisis and 2010 Eurozone debt crisis. Why not a similar approach for the crypto industry?

Looking Forward

The lesson taught by the events of the year 2022, in some cases with staggering ramifications, is that the crypto ecosystem does not need players who operate in exactly the same manner as centralised systems. To ensure this remains the case, we should continue to drive the intent put forward by Satoshi Nakamoto, a point clearly made by Odera Ume-Ezeoke, Founder and CEO of Elbow, who said:

Recent turbulence and events in the crypto world have served a reminder on the dangers of entrusting our investments to centralised entities. Consequently, it’s no surprise that we are seeing a resurgence of interest in DeFi, as its transparency and permissionless nature offer a safer and more reliable alternative for investors.

When I reflect on the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023, I intend to consciously maintain my excitement and optimism about the crypto ecosystem and DeFi. Although I resolve to no longer ask for whom the bell tolls in the months to come, I will make every effort to ensure that in my little corner of the ecosystem I conduct my enhanced due diligence, such that if and when the bells toll next, they would not toll for me or the projects I may find myself involved in.

G0xse is a UK Regulatory Lawyer interested in DeFI, Crypto Regulations and DAOs with a consulting practice assisting founders, crypto startups in areas such as business strategy, regulatory compliance, jurisdiction preference and legal entity structures for DAOs. She is a member of BanklessDAO’s Legal Guild, LexDAO, the Blockchain Barristers Discord. Connect on Twitter, LinkedIn, or at dikaiosltd@gmail.com.

Attorney-Client Privilege in DAOs and Other Digital Spaces

Author: lawpanda

The attorney-client privilege protects a confidential communication made between privileged individuals (i.e. an attorney, a client, or an agent) for the purpose of obtaining or providing legal assistance for the client. Most communications or exchanges between an attorney and client are covered by the attorney-client privilege. Privileged communications include any expression undertaken to convey information in confidence for the purpose of seeking or rendering legal advice.

The underlying principle of attorney-client privilege is to provide for “sound legal advice [and] advocacy.” Relying on the inherent security of the privilege, a client may speak frankly and openly to legal counsel, disclosing all relevant information to the attorney without fear that the information may later be used against them, thus allowing the attorney to effectively and efficiently represent the client.

The attorney-client privilege is both a professional conduct requirement for attorneys and an evidentiary standard applied by courts. Professional conduct obligations while representing clients in the digital space are the primary focus of this article. Note that the article provides a generalized overview and does not constitute legal advice.

While varying in substantive and procedural parameters, privilege requirements apply to attorneys in all jurisdictions. While the exact parameters may vary, disclosure — whether intentional or inadvertent — to a third party will generally remove or invalidate privilege.

In the past, clients would meet with their counsel in person, and most client information was maintained at a law firm’s office in paper files. In that context, the application or waiver of privilege is fairly straightforward. Maintaining attorney-client privilege in the context of today’s variety of electronic communication mechanisms and platforms is far more nuanced. As the use of various technologies, including immersive digital environments, increases, it is particularly important for attorneys to stay informed and proficient in their use. Additionally, new organizational technologies that enable financial and human capital organization in the form of decentralized autonomous organizations can create issues for attorneys attempting to represent these entities, both in identification of the client and maintenance of privilege.

Identifying the Client: Generally

The client must be a legal person, whether an individual or a legal organization registered with the state, like a corporation. In the corporate context, the client is the corporation. Even though the stockholders own the corporation, and the directors, executives, and employees are directly involved in the attorney-client relationship, may act upon the advice received, and can incur personal liability for their actions taken pursuant to that advice, only the corporate entity — the legal fiction that is the creation of the state — is considered the client.

The application of the attorney-client privilege to communication between unincorporated entities, such as partnerships and trade associations — or more importantly DAOs — and their legal counsel, gives rise to the question: who or what personifies the represented entity? For an association or partnership, the ‘who is the client’ question is usually answered differently than for a corporation. This is also likely the case for DAOs that are not incorporated or associated with a legal entity.

Courts have previously found that the attorney for an association or partnership and each member have a direct attorney-client relationship, just like they have with other unincorporated groups that have no existence apart from their members. However, courts have been wary of making a blanket pronouncement about the extent to which members of unregistered organizations can hold privilege on behalf of the organization, preferring to make case-by-case decisions based on assessment of whether confidentiality could reasonably be expected by the members of the association under the particular circumstances of each consultation. This uncertainty can make representation difficult from the perspective of an attorney representing an association, DAO, or other organization without an associated legal entity. It is arguably hard to maintain privilege with an unincorporated organization when the determination is dependent on jurisdictional rules or after-the-fact court rulings.

Identifying the Client: DAOs

The DAO is a non-entity technological structure that facilitates social coordination and collective online decision-making. DAOs are, by definition, community-led with no central leadership and built on a blockchain using smart contracts. Unlike traditional corporate structures, DAOs do not inherently maintain fictional legal personhood, which can complicate the representation of the DAO by attorneys.

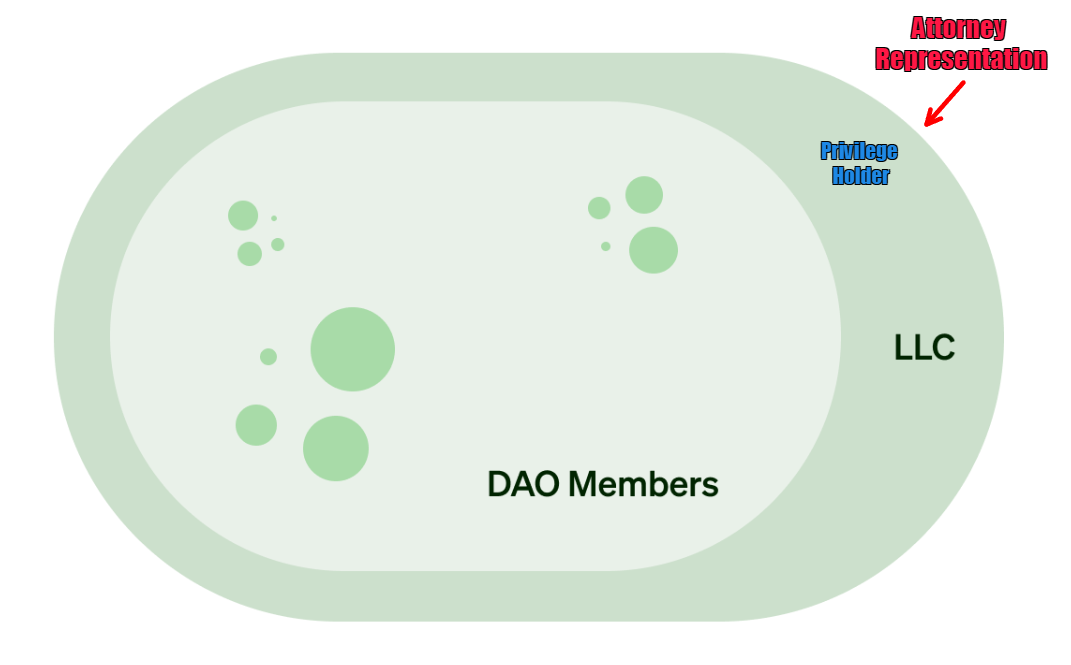

In the ongoing CFTC action against Ooki DAO, the CFTC alleges that Ooki DAO is an unincorporated association — also sometimes characterized as a general partnership. The California Evidence Code recognizes members of unincorporated associations as holders of privilege against third parties. In this type of case, an attorney who represents members of an unincorporated association will usually be considered to represent each individual member of the association in matters of association business. A visual representation of the attorney-client relationship in the context of who holds privilege is provided using a modified version of Paradigm’s DAO Legal Entity Matrix, below.

What this means is that each member of an unincorporated association has an attorney-client relationship with the association’s attorney, and each member can claim the privilege or waive it, at least with respect to an external challenge to privilege. The ability to maintain privilege during internal disputes is less likely, if not non-existent. Where a DAO has been ‘wrapped’ in a limited liability company registered with a jurisdiction, privilege will be held by the entity.

In a third iteration, where the DAO directs a siloed entity but is not considered “wrapped,” privilege will be held only by the entity, and privileged information can be disclosed only to the specifically named DAO LLC member(s) directing the entity. There is also the potential that the DAO LLC is considered a member of the unincorporated association/partnership and privilege is held with the other members.

The structure and who holds privilege is particularly important because in some instances where it may be appropriate to disclose certain information to all members of a fully wrapped DAO, disclosing that same information to members of a partially wrapped DAO could waive privilege. There is also the additional nuanced question of the extent to which DAO members of a fully wrapped DAO (where the DAO contract is the sole member of the LLC) can maintain privilege if confidential information is disclosed in non-secure forum or Discord channels. In that situation, it may be most appropriate for the DAO entity to appoint leadership to interact with attorneys to ensure privilege is maintained.

Ultimately, when representing DAOs, a group of founders, or individuals organized as — or having defaulted to — a partnership, it is important to identify the client(s) and scope of representation in any engagement documents and to rigorously maintain siloed lines of communication. It may also be necessary to assess privilege requirements in more than one jurisdiction where remote communications may be occurring.

Protecting Attorney-Client Privilege in the Metaverse

As with remote legal practice, as commerce extends in the metaverse, the legal profession will need to keep pace with technology. This topic was thoughtfully addressed by LexDAO members Elizabeth Shubov and Scott Stevenson J.D. in Five Guidelines for Maintaining Attorney-Client Privilege in the Metaverse. With the development and increased adoption of immersive work environments by Microsoft, Meta, Roblox, and web3 companies, the risks associated with data exposure and the unintentional waiver of attorney-client privilege protections become more critical. As meetings in the metaverse become commonplace, a client without proper guidance may unknowingly waive their right to claim the attorney-client privilege. To ensure privilege is protected and maintained, attorneys and organizations need to be cognizant of the technology they are using and put in place appropriate controls, including maintaining up-to-date internal procedures, cybersecurity protocols, and training for both staff and clients to prevent accidental disclosure.

Best Practice Considerations for Digital Practice

In the United States, Comment 8 to the American Bar Association (ABA) Model Rule of Professional Conduct 1.1 (Lawyers Duty of Competence) outlines an attorney’s obligation to maintain technological competency in legal practice. The Comment reads:

To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education and comply with all continuing legal education requirements to which the lawyer is subject.

While ABA Model Rules are only guidelines, iterations of their general requirements can be adopted on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis. For example, the majority of U.S. states have made it a requirement for lawyers to be “technologically competent” and keep up with changes in law practice and legal technology consistent with Model Rule 1.1 Comment 8.

The requirements of Model Rule 1.1 Comment 8 are particularly important in post-COVID remote practice and practice in the metaverse. Technology offers convenience and efficiency but also creates potential ethical landmines for attorneys who fail to understand the technology they are using. ABA Formal Opinion 498 provides a thorough discussion of the legal and ethical issues of virtual tools, along with generalized guidance as to how to avoid or minimize ethics problems in digital practice. Technological competence requires understanding the benefits and disadvantages of technology, and a focus on client confidentiality is fundamental to maintaining an ethically compliant remote or virtual workspace.

Opinion 498 discusses technologies that have become more commonplace, such as virtual meeting and document platforms, and the need for greater supervision of both employees and vendors that might allow inadvertent disclosure. To protect attorney-client privilege, law firms must educate their clients and staff on how the privilege works so that they can avoid intentional and inadvertent disclosures, as well as the risks that come with disclosure of confidential information. The standard for the protection of client information and communications is usually “reasonable care,” but what constitutes reasonable care is not always an easy question to answer and includes a variety of factors. To that end, the following internal controls and best practices should at least be considered when using technology to communicate with clients, electronically or in the metaverse, in order to remain compliant with professional conduct obligations.

Client Agreement and Education

First and foremost, clients should be educated regarding their role as clients and their ability to waive the privilege that they hold. Clients can waive privilege by forwarding an email to a friend or family member, by using unsecured platforms, by posting privileged information on social media or in online forums, or simply by entering into a discussion with an external party. Education can range from a brief discussion with an experienced client, to a written disclosure acknowledged by the client. Regardless of the mechanism, client education is important and necessary to ensure attorney-client privilege is maintained.

Attorneys also should consider including third-party technology disclosures in their fee agreements. This allows clients to make an informed decision regarding what and how vendors are handling their confidential information. This issue is addressed in ABA Formal Opinion No. 483 which provides:

Model Rule 1.4 requires lawyers to keep clients “reasonably informed” about the status of a matter and to explain matters “to the extent reasonably necessary to permit a client to make an informed decision regarding the representation.” Model Rules 1.1, 1.6, 5.1 and 5.3, as amended in 2012, address the risks that accompany the benefits of the use of technology by lawyers. When a data breach occurs involving, or having a substantial likelihood of involving, material client information, lawyers have a duty to notify clients of the breach and to take other reasonable steps consistent with their obligations under these Model Rules.

Should there be a data breach or other vendor issue, a client will not be surprised when they are put on notice of the breach and apprised of their rights, if any, against the vendor.

Finally, many clients also want to communicate via text message or other messaging services. In the DAO and crypto space, many communications take place using Discord, Telegram, and Signal. Attorneys that correspond with clients via texting or other messaging systems should remember that not all of those messaging systems are end-to-end encrypted. Implementing a strict protocol governing the appropriate use of messaging with clients is advisable to protect and preserve privilege.

Internal Policies and Procedures

Attorneys should implement internet usage policies to clarify the circumstances, if any, under which employees are allowed to use the internet, open attachments, download from the internet, or use social media. Potential internal controls could include:

Employing password protection on devices and individual documents, this includes USB flash drives.

Multi-factor authentication for device and account logins.

Only drafting and storing electronic documents on the firm’s network, rather than personal home computers.

Including settings that allow remotely wiping devices if they are lost or stolen.

Scrubbing all metadata prior to transmitting documents to external email addresses.

Strong Passwords

Passwords should be complex and include numbers, upper- and lower-case letters, and symbols, and they should also be long. Staff should be instructed not to use confidential information in creating passwords, such as birth dates, children’s names, or other easily discernible information. External vendors can assist in creating, maintaining, and changing strong passwords.

E-mail and Messaging Encryption

Email doesn’t travel in a straight line from your computer or phone to your client. It might be intercepted while it travels through servers in various countries. The best practice is to use an encrypted email service. Most email applications use some form of encryption, however there are also more robust end-to-end encrypted email services including Skiff, Tutanota, and ProtonMail.

End-to-end encrypted messengers also fall clearly in the space of an expectation of privacy between a client and their attorney. An end-to-end encrypted messenger is a messaging app that uses end-to-end encryption to keep messages secure. This means that only the attorney and recipients can read messages sent back and forth, and no one else — not even the technology provider — can access them. There are several different end-to-end encrypted messaging apps available, but some of the most popular ones include Signal, WhatsApp, and iMessage.

Digital Devices

The rapid evolution of communications technology and the means of intercepting confidential communications have created significant risks to the attorney-client privilege. Before using a device — be it a phone, tablet, or laptop — counsel and their client must be familiar with the security implications stemming from the device and any downloaded apps.

An attendant concern stemming from 24/7 email and messaging access on mobile phones includes the extent of permissions granted to an email provider’s app and how these may be violative of privilege. In a recent opinion, the New York State Bar Association’s Committee on Professional Ethics, Opinion 1240, addressed this question and concluded that:

If ‘contacts’ on a lawyer’s smartphone include any client whose identity or other information is confidential under Rule 1.6, then the lawyer may not consent to share contacts with a smartphone app unless the lawyer concludes that no human being will view that confidential information, and that the information will not be sold or transferred to additional third parties, without the client’s consent.

Unfortunately, many attorneys are not aware of the extent to which different apps can potentially see client contact information if granted access. Venmo, Facebook, Zoom, Snap, Slack, Tinder, Signal, Pinterest, Telegram, Chase Bank, Wayfair, and even Samsung’s smart washing machine will ask you for access to your contacts. This may mean that not only attorneys, but also staff, are disclosing potentially confidential information simply by having access to firm email or other messaging on their mobile devices.

Additionally, in the same way that law firms shred printed client data, attorneys should consider thoroughly wiping and overwriting data storage devices, phones, tablets, and computers used by the attorney and staff.

Data Storage

Cloud-based data storage can be an efficient and effective way to gather, share, and transmit client data. Common vendors include DropBox, Google Drive, and OneDrive, but there are many others, each with varying levels of encryption and security. As discussed previously, the potential that a storage provider could be hacked involves risks to confidentiality, and clients should be aware of those third-party risks. As with email transmission, one technical step that can be taken is to ensure client data is encrypted during transit and storage.

Secure Networks

Unencrypted data can be viewed by anyone who has network access and wants to see it. Using a virtual private network (VPN) hides your device’s IP address by letting the network redirect it through a specially configured remote server run by a VPN host. A VPN connection disguises data traffic online and protects it from external access; hackers and cyber criminals can’t decipher this data. Use of a VPN is particularly important when accessing any third-party or public WiFi service, whether for browsing the web, attending a video-conference, or just emailing.

Video Conferencing

An unsecured video conference is analogous to inviting passers-by from the street to attend an in-person client meeting. In virtual settings, attorneys should consider the following precautions:

The platform should have appropriate encryption.

Meeting links should be private and include unique links and passwords for each meeting.

Attorneys should attempt to ensure that only parties who are supposed to be attending can see or hear the conversation. Participants should join from a separate physical space, such as a room or office, and use headphones to keep other people, including family members, from seeing or hearing the communication. Unfortunately, the duty of confidentiality does not extend to family, roommates, or neighbors accessing client data or overhearing client meetings.

Meetings should occur on a private network and, ideally, public WiFi should not be used. However, if a private network is not available, the participants should use a VPN service, one that will not collect user data, to limit unwanted access to the communication.

The attorney should ensure that recording is disabled before the meeting starts, or at least configured so that the attorney is the only one allowed to record. Recording privileged communications can be problematic because if the recording is accidentally shared with a third party, or if proper measures are not taken to ensure that the recording is secure from a third party (e.g. either in the cloud or locally), this may waive privilege.

Participants should turn off listening devices such as Google Home or Alexa.

To the extent that these safeguards can be enacted, attorneys should consider which are appropriate and necessary in the context of their practice. While these safeguards may not be necessary for every practice, failing to implement readily available safeguards could later be used as a basis for challenging privilege or, even worse, considered an ethical breach, and unfortunately, getting disbarred in the real world carries over to the metaverse.

lawpanda is a U.S. attorney with an active litigation and counseling practice assisting builders, developers, traditional companies, and decentralized communities. He is a member of BanklessDAO’s Legal Guild, LexDAO, LeXpunK, the Blockchain Lawyers Group, and member/consultant/contributor to a variety of DAOs and protocols. When he’s not writing for Decentralized Law, he is working to reduce operational and governance friction between on-chain and legacy entities through corporate structuring and common-sense legal solutions. Read his scribblings on Mirror and connect on Twitter, LinkedIn, or at lawpanda.eth@gmail.com.

🏛 Regulations

The Nexus Between NFTs and Money Laundering

Author: Svetlink

As an object of legal qualification and ruling, NFTs have received well-deserved attention from the EU policymakers in the Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) regulation. The rules are clear that MiCA does not apply to unique and non-fungible crypto-assets. However, a detailed explanation of how an asset is determined to be a NFT is yet to come. The European Banking Authority is commissioned with providing definitions and clarifications on the “indicator of fungibility”.

Across the Atlantic, it has been challenging for U.S. legislators to pass specific NFT regulations. They struggle to differentiate between NFTs as digital representations of real-world objects, bought, stored, and swapped between collectors; and other digital assets. Questions remain about how they should be regulated and whether some NFTs are securities. Legislative specifics of this kind are outside the scope of this article.

Amid the global storm of regulatory maneuvers, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has cemented its role as an international standard-setting body for financial activities involving virtual assets. In the latest Guidance published in June 2022, the organization notes that NFTs that are unique and used in practice as collectibles rather than as payment or investment instruments are not virtual assets for purposes of the FATF standards. For those NFTs, the strict AML/CFT requirements shall be excluded in general. Nonetheless, once the virtual assets benchmark is triggered, i.e. the NFT is found to be widely used for payment or investment purposes, the jurisdiction should apply the high-level standards typical for the operations with virtual assets. In effect, FATF opened the door for a big digital artwork party but placed a solidly built bouncer in front of the clubhouse.

So far, no strict rules have been observed. Of course, there is no complete happiness, right? Alongside a sweet influx of funds into NFT marketplaces, complex scams amounting to over $100 million were publicly reported between July 2021 and July 2022, casting a shadow in that way over the market stability.

All the figures, graphs and visualizations in this article are sourced from the reports of two prominent blockchain analysis providers: Chainalysis and Elliptic.

What Do the Rule Books Say?

NFT marketplaces were not directly subject to the EU’s Anti-money Laundering Fifth Directive published May 30, 2018. The NFT business model was not sufficiently understood at the time these rules were implemented. At the same time, the scope of the Directive is broad enough to cover the exchange of NFTs for cryptocurrency.

To the extent that NFT businesses resemble conventional art dealers, they fall within the scope of the Directive along with virtual currency exchange service providers. Anyone involved with trading or intermediation in the trade of works of art for more than 10,000 EUR must build a reliable customer due diligence program, apply a risk-based approach to their clients, and report any suspicious activity.

In February 2022, the U.S. Department of Treasury brought some clarity to money laundering vulnerabilities of digital art markets. Their Study introduced NFTs as “digital units, or tokens, on an underlying blockchain that represent ownership of images, videos, audio files, and other forms of media or ownership of physical or digital property; bearer instruments that codify the ownership of a unique digital asset, such as a piece of high-value digital art and are managed via smart contracts and digital wallets”. The imminent threat comes from the characteristics of virtual assets and the structure of transactions with digital art.

For example, a NFT purchased by a criminal with ill-gotten funds can be used for a transaction with an unsuspecting bona fide buyer. The transfer of ownership between digital wallets or smart contracts is publicly verifiable and auditable on a blockchain, which gives the bad actor a legitimate explanation for the sale and cuts the ties with a previous crime. Transaction velocity along with the absence of third-party services like shipping, insurance, or customs representatives makes it even more convenient for the criminal to launder the money and get a safe exit without leaving administrative trails.

Another factor is the smart contracts that are used to govern the ownership and transferability properties of NFTs which can be set up to generate revenue each time a NFT transaction is recorded on a blockchain. Certainly, the artists would get fair compensation for their work in this way, but it would also create an incentive for running a marketplace where rapid transfers are possible without diligent assessment of the deal, customer verification, or transaction monitoring. Such a hypothetical scenario involves an increased risk of money laundering due to an unrealistically high volume of transfers, non-compliance with AML/KYC principles, and lack of technical understanding of blockchain technology required to practice effective customer due diligence in this space.

Consistent with the FATF Guidance, the Treasury’s Study stated that collectibles which do not meet payment or investment instruments qualification criteria should not be considered virtual assets under the FATF definition. Regardless of the treatment of the object of exchange, some NFT platforms may still qualify as VASPs. Depending on the characteristics of the NFTs that they offer or the market they operate in, the platforms could be exposed to stringent AML/CTF regulations e.g. obligations under the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)’s rules for money service businesses if they are doing business in the United States.

Washing Off JPEGs

With around $44.2 billion worth of cryptocurrency sent in 2021 to ERC-721 and ERC-1155 contracts — Ethereum smart contracts associated with NFT marketplaces and collections — criminals had plenty of opportunities to experiment with the developing sector. The two main forms of illicit activity observed by Chainalysis are wash trading to artificially increase the value of NFTs and money laundering through the purchase of NFTs.

Wash Trading

As defined by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the term means "entering into, or purporting to enter into, transactions to give the appearance that purchases and sales have been made, without incurring market risk or changing the trader's market position". Using NFTs, the goal would be to pump the price of the piece of digital art by making a fictitious sale to a new wallet under his/her control and ownership. As long as many NFT trading platforms allow users to trade by simply connecting their wallet to the platform, with no need to identify themselves, it will be easy for the bad actor to make the NFT look more valuable than it really is. A thorough blockchain exploration led by Chainalysis reviewed NFT sales to self-financed addresses, meaning they were funded either by the selling address or by the address that initially funded the selling address. Investigation revealed hundreds of wash trades carried out in this manner.

In a typical wash trading case, one would perform multiple transactions in a rapid consequence without taking market risk. The simplest form is one address quickly reselling an NFT at a price much higher or lower than the purchase one. Selling low may be reasonable for the wash trader who aims to report a loss for tax purposes, for instance.

More sophisticated cases investigated by Elliptic involve a bunch of addresses interacting with each other. They may belong either to the same user or to close associates. Distinctive for this kind of activity is а series of contemporaneous transactions: address A sells NFT to address B, which in turn instantly transfers back to address A.

Sometimes wash traders abuse NFT popularity for financial gains. A popular concept for increasing virtual asset prices is promotion through various publications, articles, reviews and online discussions. In a situation where vanity is generated through notable trades, users can blindly follow the trend and drive up the price for future sales; as an example see the sale of Cryptopunk #9998 for 124,457 ETH ($532 million).

Another typology for overvaluation is observed with projects and marketplaces that have active-user reward programs. Usually, users are incentivized to stake, swap, or trade on the platform for remuneration in the form of a specific platform-native token. To the extent that the program is built around trading volumes, traders may deliberately overvalue their NFTs to maximize the rewards. Elliptic pointed out the manipulation of Meebit #13824, with trades of up to $50.6 million (321,099% above the floor price).

The existence of NFT wash trading is something of a murky legal area that has not yet been approached by law enforcement. In contrast, a prohibition on wash trading of conventional securities and futures has been in place going back to the Commodity Exchange Act in 1936. Similar reliable boundaries could be set once regulators start applying existing anti-fraud and money laundering preventive measures to new NFT markets.

Good Old Money Laundering … in Fancy Clothes

Bearing in mind that NFT price performance is strictly dependent on community support and larger market trends, someone with a vested interest in manipulation could easily benefit from these factors. Pieces of digital art predominantly consisting of cartoon-style, computer-generated JPEGs could arguably be considered worthless….or priceless.

It is the volatile value and utility characteristics of NFTs that make them highly vulnerable to trade-based money laundering. FATF defines trade-based money laundering as "the process of disguising the proceeds of crime and moving value through the use of trade transactions in an attempt to legitimise their illicit origins." This result may be achieved through the misrepresentation of the price, quantity or quality of traded assets. A typical example is a fraudulent invoice issued by one of the conspiring parties allowing the other — the recipient of goods — to either overpay or underpay depending on the projected cash flow. The outcome of the fraudulent scenario is invoicing and transfer of funds under the guise of a commercial transaction.

Luxury items, including those that are digital, are a prominent vehicle for money laundering due to the ease with which the price or quantity can be manipulated. Thus the source of illicit wealth may be justified through legitimate NFT trading. The tax authorities or financial institutions usually do not have the ability to verify the objective price of the NFT and logically encounter difficulties determining whether the person’s explanation is reasonable and legitimate.

Elliptic revealed a wallet that allegedly stored phishing scam proceeds amounting to $1.2 million with significant trading volumes on UniSwap. On January 28, 2022 a Bored Ape NFT was purchased using $435,000 of the wallet balance — a textbook case of legitimizing illicit income. Being the most expensive NFT collection at the time, Bored Apes became attractive for storing and justifying illicit funds because of the collection’s high value and low risk.

Trade-based money laundering techniques flourish in complexity and are frequently used in combination with other money laundering techniques to further obscure the money trail. Launderers rarely resort to direct deposits with centralized platforms or marketplaces without first disguising the illicit proceeds. For the purpose of obfuscation, criminals will choose mixers (websites or software used to create a disconnection between a user’s deposit and withdrawal), P2P exchanges (platforms that facilitate the cryptocurrency exchange between two individuals while the intermediary is not in direct possession of the funds and does not require any KYC), or crypto ATMs (they operate similar to normal fiat ATMs but certain KYC deficiencies may be exploited). These services, which are usually labelled by reputable blockchain analytics solutions as providers posing medium to high risk, grant the perpetrators the opportunity to disassociate themselves from the underlying criminal activity and break their transaction trail. Exposure of NFT platforms to ETH originating from obfuscating sources between Q4 2017 and Q2 2022, as measured by Elliptic, counts up to $137.6 million for mixers and $133.9 million for cross-chain bridges.

Тo draw a clear line of demarcation: the use of these services does not imply that the user is a criminal or that their funds are illicit. There are many legal uses of said services, from privacy protection through online gambling to deeper adoption of blockchain protocol tokens.

The Sanctions Trap

In 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued an Advisory to emphasize the sanctions risks arising from dealings in high-value artwork associated with persons blocked pursuant to OFAC’s authorities, including persons on OFAC’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List). When read along with FinCEN’s advanced notice of proposed rulemaking for dealers in antiquities, it could be established that NFTs show certain features typical for high-value art and collectables that may be exploited by money launderers and terrorist financiers to evade detection by law enforcement. These characteristics include client confidentiality or unregulated customer due diligence practices, varying practices in accurately documenting provenance, subjectivity of prices, and predisposition to be used to transport value across borders without reporting to authorities or detection by law enforcement agencies.